The Best Temporary Exhibits to See Now in Washington, D.C.

Please check back soon for updates.

Exhibits in Washington, D.C.: Closed

Helen Hayes (Folies Bergere) Theater, terra cotta from facade. Gift of Landmarks Preservation Commission. Photo by NBM staff.

Cool and Collected

This mid-sized exhibit is chock full of interesting objects, a welcome relief at a time when many exhibits are too reliant on text and reproductions of photographs. It highlights a wide variety of artifacts and collections recently acquired by the museum, giving some insight into how a relatively new museum (opened in 1985) is building its collection. Visitors will see the architectural model of an addition to the Corcoran Gallery of Art planned by Frank Gehry but later cancelled for lack of funds. (The Corcoran closed permanently in 2014.) There is a collection of colorful terra cotta fragments from prominent buildings long since demolished, and a fine ink-on-linen plan for the National Cathedral from 1906.

In a separate room is a sampling of a collection of paper models of buildings donated by David Kemnitzer, a local architect. Kemnitzer started collecting the models as a boy, and they inspired him to pursue a career in architecture. The paper structures run all the way from "Rinty's own Fort Apache" on the back of Cheerios box to a four-foot-tall model of the Sears Tower in Chicago. Also on display is a collection of plaster models that Ray Kaskey made for his sculptural work at the World World II Memorial in Washington and elsewhere. A trip to the National Building Museum is valuable for no other reason than its central Great Hall, one of the most impressive interior spaces in the city, and its outstanding gift shop.

National Building Museum

401 F Street, N.W., Washington, D.C.

Admission: $10 adults with various discounts available

Through early April 2018

Johannes Vermeer, The Lacemaker, c. 1670-71. Musée du Louvre, Département des Peintures, Paris. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée du Louvre)/Gérard Blot.

Vermeer and the Masters of Genre Painting

Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675) was largely forgotten before his work was rediscovered by art historians in the late 19th century. Experts have argued ever since about precisely which paintings can be attributed to Vermeer, but the consensus is about 35, a small number compared to many of the artists of his time. Ten of his works are on display in this temporary exhibit at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, along with more than 50 works by his Dutch contemporaries, including Gerard ter Borch, Gabriel Metsu, and Gerrit Dou.

Vermeer is best known for his genre paintings—scenes of everyday life in which men and women go about their daily business—where the subject is caught writing a letter or working a bit of lace, seemingly lost in thought. His work is remarkably similar to that of painters such as Ter Borch, but Vermeer remains the best known of the group because of the magical quality of the light that illuminates his subjects. Rather than simply charting the path of Vermeer's career, this exhibit explores the ways in which he and his contemporaries influenced each other's work.

National Gallery of Art

West Building, Constitution Avenue and Sixth Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C.

Through Jan. 21, 2018

Admission: free

Peacock Room REMIX: Darren Waterston's Filthy Lucre

Filthy Lucre is a room-sized installation that you can walk into, a reinterpretation of the famous Peacock Room in the adjacent Freer Gallery. The latter is itself a work of art created by the American artist James McNeill Whistler in 1876. Filthy Lucre is Whistler's room as a magnificent ruin, but more. It's the room reimagined, not quite how the Peacock Room would really appear in a state of decay, but in some alternate reality. The pots are shattered, the shelves broken and tilted, and there are weird globs of thick gold paint dripping to the floor.

Unfortunately, you won't be able to see the original Peacock Room because the Freer Gallery of Art is closed for renovations, but a virtual tour is available online here. The Peacock Room was originally installed in the London home of Frederick Leyland, who displayed his collection of Chinese porcelain there. The centerpiece was Whistler's painting The Princess from the Land of Porcelain. Leyland allowed Whistler to retouch the room to harmonize with the painting, then left town. The temperamental artist got carried away, covering every surface with blue, green, and gold paint. Whistler topped it off by presenting Leyland with a huge bill.

The fight over the room ruined their friendship, and Whistler, bankrupt, feared that Leyland would seize his studio. The artist painted a caricature of Leyland as a lizard-like peacock playing the piano, surrounded by bags of money. Its title was The Gold Scab: Eruption in Frilty Lucre (The Creditor)—Leyland was an accomplished amateur pianist who favored frilly shirts. Darren Waterson was inspired by The Gold Scab and the collision of art and commerce that it evokes. Filthy Lucre reflects Whistler's excess, the friendship gone bad, and especially the impact of money on art—Whistler's Peacock Room has mutated much as our overheated contemporary art market has been distorted by money. Waterston's room is accompanied in this exhibit by Whistler's two paintings, Princess from the Land of Porcelain and Gold Scab, and some of Waterston's preparatory sketches.

Sackler Gallery

1050 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C.

Through January 2, 2017

Photograph: Photograph by John Tsantes, Freer/Sackler

1856 British Guiana One-Cent Magenta

This may be your only chance to see the world's rarest postage stamp, which sold in 2014 for $9.48 million. Only one of these is known to exist, and it has a fascinating backstory. The stamp was found by a 12-year-old Scottish boy in British Guiana in 1873 and sold soon thereafter for a few shillings. Now on loan from its current owner, the one-cent magenta is displayed in a small, dimly lit case protected by an armed guard. This might also hold the record for the world's most underwhelming museum exhibit: The stamp was printed in black ink on a dark red background, so it's difficult to see much of anything, although you might be able to make out its octagonal shape. In any case, you will want to visit this museum if you have any interest at all in stamps or postal history.

National Postal Museum

2 Massachusetts Avenue, N.E.

Through November 2017

Photograph: Smithsonian's National Postal Museum

Exhibition The Greeks: Agamemnon to Alexander the Great. Photo by Mark Thiessen/National Geographic

The Greeks: Agamemnon to Alexander the Great

Organized in cooperation with the Greek Ministry of Culture and Sports, this exhibit showcases 500 artifacts from 22 Greek museums. It is billed as "the most comprehensive exhibition about ancient Greek history to ever tour outside of Greece," and covers a 5000-year span from the Neolithic to the death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C.

The focus here is on archeology and history. Many of the 500 objects are funerary goods: weapons, armor, jewelry, and ceramics that were placed in graves. There are works of art and some objects of great historical interest. Among them is the famous mask of Agamemnon. At the end of the 19th century, the German archeologist Heinrich Schliemann excavated the ruins of Mycenae, in Greece. Schliemann hoped to find the grave of Agamemnon, the mythic conqueror of Troy in Homer's Iliad. When Schliemann found a spectacular gold funerary mask, he pronounced it the face of Agamemnon. When he found a second and even more impressive mask, he decided that it must be the true mask of the king. The first mask is here, and the second is represented by a unique copy made of gold. Neither could be the face of Agamemnon though. The masks date from the 16th century B.C., hundreds of years before the Trojan war on which the Iliad might have been based.

A Gorgon, a mythological creature, from the armor of Philip II. © Museum of the Royal Tombs of Aigai, Vergina

Another spectacular object is a gold wreath that belonged to Meda, the wife of Philip II, king of Macedon, who unified Greece in the 4th century B.C. Philip's son, Alexander the Great, went on to conquer Persia and much of the Near East. The exhibition ends with Alexander's death and the beginning of the Hellenistic period, which was marked by the diffusion of Greek culture through a vast area and the growing political influence of Rome.

Most visitors will need several hours to get a thorough look at this exhibit, which covers thousands of years and several great civilizations: the Minoans on Crete, Mycenae, and classical Greece (480-323 B.C.). The latter, of course, held the beginnings of Western civilization. The Greeks invented democracy, philosophy, theater, the systematic study of science, and so much more that has come down to us today. The exhibition has a nice balance of wall text and objects, and the text is clear and informative. Visitors who who are new to ancient Greek history would get more out of the exhibit by first watching the three-part documentary The Greeks, produced by National Geographic and broadcast on PBS.

National Geographic Museum

1145 17th Street, N.W.

Washington, DC 20036

admission: $15 adults with various discounts available

closed October 10, 2016

Hubert Robert; The Old Temple, 1787-1788; oil on canvas; The Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of Adolphus C. Bartlett

Hubert Robert, 1733-1808

Hubert Robert, a French painter active during the decades before and after the French Revolution, was a master of the capriccio, an architectural fantasy in which disparate buildings, statues, and monuments from antiquity were brought together into imaginative new compositions. Robert came from humble origins, but he was an amiable, and erudite, bon vivant who moved in the highest social circles.

As a young man, Robert spent 11 years in Rome, studying art and sketching the many ruins there—sketches that he would rely on for many years to come. Robert was known to his friends as Robert des Ruines. In his paintings, the monuments of past empires lie abandoned, their broken vaults open to the sky while weeds push outward from cracks in the stones. Peasants wander through the scene, oblivious in their daily routines.

After he returned to Paris, he would sometimes paint an ensemble of canvases for a single room and coordinate them with the colors and furnishings. The effect must have been spectacular—one such group of four monumental paintings is on display here. Robert reminds us of the fleeting nature of all things on earth—our own brief lives most of all. His paintings gathered here are enjoyable but, sometimes, can seem a bit too easy or decorative.

Robert managed to survive the revolution, just barely, and some of his most compelling works show the destruction in Paris during those times. The Marquis de Lafayette so admired his painting of the demolition of the Bastille that Robert gave it to him. After the revolution, Robert became the curator of the Louvre. The last room of the exhibit—there are seven—is devoted to his paintings of the Louvre, both in the present as an art gallery and in a distant and imagined future as a magnificent ruin.

National Gallery of Art

600 Constitution Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C.

admission: free

through October 2, 2016

Reporting Vietnam

This exhibition, about press coverage during the Vietnam War, marks the fiftieth anniversary of the start of the war for the United States. The year 1965 is a bit arbitrary since the American role increased incrementally, but it was the first year that U.S. ground troops were sent into combat. The exhibit shows how news coverage evolved as the media first supported and then turned against the war, both reflecting and helping to mold public opinion. There are a number of interesting artifacts, including the camera and typewriter that Peter Arnett used during his years in Vietnam. There are two excellent videos about TV coverage of the war. Be forewarned that this is a small exhibit in a large and expensive museum. The current admission for an adult is $24.27 including tax, but there is a lot to see here. Not to be missed are artifacts from 9/11 and an exhibit on the Berlin Wall that includes the largest section outside of Germany. In the lower level is a fascinating exhibit with many artifacts from the FBI related to crime and terrorism including the Unabomber's cabin and the Time Square bomber's SUV.

Newseum

555 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C.

closed Sept. 12, 2016

Photograph: Photographers huddled behind a log. Courtesy Steve Northup

Wonder

The Renwick Gallery reopened in November 2015 after a two-year renovation. Wonder is the inaugural exhibition, and it is setting records for attendance. Each of nine galleries holds one large artwork made by a different artist for the space. The works are meant to evoke a sense of wonder, and indeed they do, by their great size and intricate detail. Most were constructed from thousands of separate pieces, and the labor that must have been involved is stupefying.

Wonder is that "right brain" experience that you get when you stop in your tracks as you enter the room and stand for a moment in speechless amazement. Exactly what that is and how it should be interpreted has been a topic of discussion for millennia—the wall text here briefly mentions it, while the published catalog goes into more detail.

On the second floor is John Grade's Middle Fork (Cascades). The artist made a plaster cast of a 150-(or so)-year-old hemlock tree in the Cascades, a nod to the age of the newly renovated building. More than 100 volunteers carved 500,000 pieces of reclaimed old-growth cedar into tiny shapes that fit together to form a tree trunk that fills the room. Once the exhibit closes, Grade will return the piece to the forest floor to allow it to decompose. Jennifer Angus, in her In the Midnight Garden, applied thousands of tropical insects to the walls of a gallery painted red with cochineal, which itself is derived from insects. Each of the artworks in Wonder relate to the natural world in one way or another, evoking its complexity and fragility.

This exhibit is a bit out of character for the Renwick, which is the Smithsonian's museum of contemporary craft and decorative arts. Its collection includes ceramics, furniture, wood carving, metalwork, fiber arts, and the like and, in years past, it has presented exhibits on historic decorative arts. The Renwick says that it will reinstall American crafts from its permanent collection once Wonder closes.

If you pass by the Renwick at night, you will see the controversial new signs advertising the museum. Critics say the bright electric signs would be more appropriate for a carryout restaurant than a National Historic Landmark building only a few steps from the White House.

Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian Museum of American Art

Pennsylvania Avenue and 17th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C.

Photograph: John Grade, Middle Fork (Cascades), 2015. Photograph © Peter R. Penczer 2016.

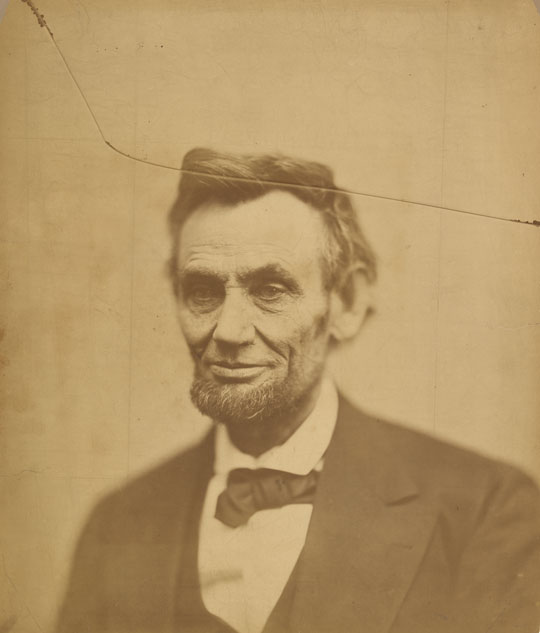

Dark Fields of the Republic: Alexander Gardner Photographs, 1859-1872

Alexander Gardner, one of the greatest photographers in American History, is known for his images of the Civil War and Abraham Lincoln. This exhibit is the first comprehensive exhibit of his work at the National Portrait Gallery. The photographs are beautifully presented in six rooms flanking a corridor. They're dimly lit to protect them from undue damage, but the walls are painted dark colors to help your eyes adjust to the darkness and pick out the fine details in Gardner's prints.

Gardner worked for famed photographer Mathew Brady, but left in 1862 to establish his own studio at 7th and D streets, only two blocks from the museum (at that time the U.S. Patent Office). Gardner made photographs of the dead littering the battlefields at Antietam and Gettysburg, which shocked the nation. He was the first to realistically portray the human cost of war, helping to nudge photography from romanticism towards modernity. Gardner was Lincoln's favorite photographer, and his famous cracked-plate photograph of the president is the centerpiece of the exhibit. It's a deeply expressive portrait of the war-worn leader, taken shortly before his assassination. Gardner made only this one print before he discarded the broken glass negative, and this is a rare opportunity to see the original.

Little is known of Gardner's life. After the war, he went out West to document a transcontinental railroad route and treaty negotiations with the Indians. That work is represented here as well, but the vast majority of the exhibit is devoted to his photographs of the Civil War, Lincoln and his cabinet, military leaders, and other important personages of the war years.

National Portrait Gallery

8th and F streets, N.W. Washington, D.C.

Closed on March 13, 2016

Photograph: Abraham Lincoln, by Alexander Gardner, albumen silver print, 1865. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World

Beyond a doubt, this is the most important exhibition in Washington this year. The curators have gathered together 50 bronze sculptures from the Hellenistic era of ancient Greece. Out of the tens of thousands that were made, only about 200 survive to the present day. Bronze works were melted down for the valuable metal, and the few that have survived were either buried by chance or lost at sea in antiquity. Phillip Kennicott, art critic for the Washington Post, wrote that this is "probably a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to study one essential aspect of the Hellenistic age."

That age began with the death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C. and continued for some three centuries. The period was marked by the expanding influence of Greek culture following Alexander's conquests. Hellenistic sculpture was more realistic and expressive than that of the Classical period that preceded it. While classical sculpture depicted gods and rulers in idealized form, the later works featured real people of all ages and classes, with real emotions that evoke our sympathies: "pathos." The most striking aspect of these sculptures is the emotional connection that we can feel with their subjects: people, just like us, who lived and died millennia ago.

Bronze sculptures are more than simply metallic versions of the more-common marble works. Bronze is stronger, so sculptors could cast figures with outstretched arms and the like that would be too delicate in marble. The sculptors started with wax models from which molds were made for the bronze castings—the wax was much easier to model and allowed for finer details in the finished works than marble.

National Gallery of Art, West Building

4th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C., between Constitution Avenue and Madison Drive

Closed on March 20, 2016

Photograph: Unknown Artist, Portrait of a Man c. 100 B.C., National Archeological Museum, Athens, Greece. Photograph courtesy of the National Gallery of Art.

Copyright © Peter R. Penczer 2019